53 Days of War in Persian Land and 8 Years of Destruction of the Non-Persian Lands

Pejvak Kokabian

Why was the continuation of the eight-year war in the lands of non-Persians not a concern for anyone? Will Persian land, located in central Iran, survive a long-term war?

Despite the passage of three decades since the end of the eight-year Iran-Iraq War (1980–1988), a comprehensive analysis from a non-governmental perspective has not yet been presented on this tragedy, which lasted for the combined duration of both world wars. A few officials and political leaders of the time have made references in their memoirs to the reasons for the beginning, continuation, and end of the war, but the narratives and memoirs are so personal and individual that many aspects and reasons for the war remain obscure and hidden to this day. In the midst of the narratives provided by Hojjatoleslam Dua’i, Ayatollah Montazeri, and military commanders, vague references have been made to the nature and origin of the war, but there has been almost no source or comprehensive analysis of the nature and origin of the end of the war.

It is important to note that some Revolutionary Guard leaders had made commitments to an international coalition before the revolution to intensify relations with their neighbors, especially Iraq. So, after the revolution, the Iranian government found itself in conflict with all of its neighbors. The most important confrontation between Iran and Iraq led to an eight-year war.

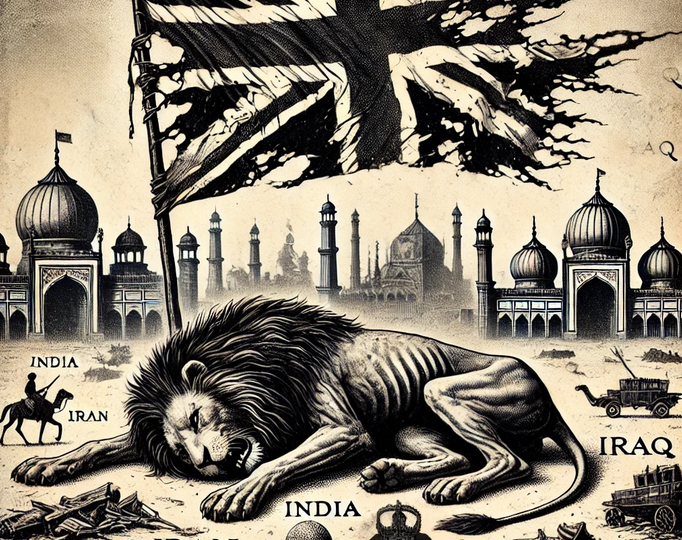

A close look at the documents and narratives exchanged three decades after this tragedy sheds light on part of the center-versus-periphery setup and colonial policies of the Iranian rulers and leaders in prolonging and continuing the war and the conditions of its end. The Iran-Iraq War continued for eight years without interruption and without serious effort or a rational strategy to end it in the lands of the Arab, Lor, and Kurdish peoples (those who share borders with Iraq), and until the flames of war directly engulfed the inhabitants of central Iran (Persian land), no serious effort was made to end the war.

The eight-year war, until the last two months, never entered the diplomatic and serious path of international forums. In fact, until Saddam’s missiles reached the cities of Tehran, Isfahan, Qom, and central Iran, the diplomatic apparatus and the regime’s leadership did not make a serious effort to accept the resolution that Iraq had accepted and that had been proposed by the United Nations. In fact, the United States and other powers proposed the 598 ceasefire plan to end the war between the two countries, but Iran rejected it. The start of Iraq’s missile and air attacks is seen as Iraq’s pressure on Iran to accept Resolution 598.

As the first missiles hit the Persian cities, Iran’s rulers began to notice the devastation caused by the war in their central cities. At the same time, sporadic protests and unrest began, which the government tried to deflect.

The Iraqi airstrike on the Tehran refinery began on Saturday, March 27, 1987, and two days later, Iraq launched a missile attack on Tehran. These missile attacks on central cities lasted a total of 53 days, and for the first time, the cities of Tehran, Qom, Isfahan, Tabriz, Karaj, and Shiraz (Persian-dominated cities) were attacked by Iraqi missiles. These attacks continued until the end of March (Farvardin) 1988.

The new round of Iraqi missile attacks was not like the previous airstrikes. Iraq, with Soviet help, had converted the solid fuel of the improved missiles into liquid fuel, so their fuel capacity was greater and their range increased. After eight years of confrontation, the first range of Scud-B missiles reached central Iranian cities, including Tehran, Qom, and Isfahan. The new round of attacks on cities was mainly missile-based and targeted Persian-majority cities.

During these attacks and missile barrages, a total of 189 missiles hit these cities, and these 189 missiles brought an end to eight years of futile war.

| City | Number of Missiles Hit |

|---|---|

| Shiraz | 3 |

| Karaj | 4 |

| Tabriz | 8 |

| Qom | 17 |

| Isfahan | 23 |

| Tehran | 134 |

The early closure of offices, schools, and universities at the end of the year and early March caused chaos and cut off the electricity and fuel distribution network in Tehran and certain central cities of Persian lands. This significantly changed the normal life of everyone, especially the citizens of the central and Persian regions, in a short period. The war propaganda headquarters, which previously always tried to sanctify and encourage the continuation of the war in a frenzied way (“War, War, to Win the War”), suddenly resorted to the strategy of magnifying the destructive effects of the war. The war media strategy, which previously emphasized hero-making propaganda and glorifying the war, shifted to public education on chemical, microbial, and nuclear defense, spreading news of chemical attacks on the regions, and abruptly changing the war’s epic atmosphere to one of defense and victimization.

Due to continued rocket fire on central Iranian cities after the Farvardin (new year, March) holiday, students were forced to study through distance learning facilities, such as radio and television. Many citizens migrated to cities far from population centers. This unplanned migration to destinations lacking facilities caused shortages of food, housing, and shelter, and disrupted the distribution of fuel, food, and the financial and liquidity systems. The Persians, government bureaucracy, and central Iran experienced the reality of war and its hardships firsthand, prompting efforts to end the war.

With the first missiles hitting Persian cities, diplomatic movements and public calls began to clarify the war situation. Traffic and political and diplomatic actions increased. BBC Radio reported from the United Nations office that “Mr. Mahallati, Iran’s representative to the United Nations, has stated that he has informed the Secretary-General of the United Nations, the UN Presidency, and the President of the Security Council that Iran has proposed that if Iraq stops attacking Iranian [Persian] cities, Iran will immediately and unconditionally end its attacks on Iraqi cities.” The Soviets probably influenced Iraqi officials to convene an urgent meeting of the Security Council. They feared that some countries would resume their demand for an arms embargo on both countries [Iran and Iraq]. Ayatollah Mousavi Ardebili, then-Chief of the Supreme Court and interim Friday prayer imam in Tehran, announced during Friday prayers on March 5, 1987, that the Islamic Republic was ready to stop its retaliatory attacks on the condition that Iraq also stopped attacking Iranian cities. But he emphasized that the war on the fronts would continue.

It is interesting that the rulers and leaders of the Iranian government and state had no problem with the continuation of the war on the fronts, periphery, and lands of non-Persian nations. Iran, in different ways, wanted to stop the missile war on cities. Esmat Kattani, in a meeting with the Secretary-General and also the President of the UN Security Council, the Iraqi ambassador to the UN, announced that Iraq had accepted Resolution 598, and it was the Islamic Republic of Iran that had rejected it.

The Iraqi Baath Party’s Command and Presidency Council stated in a meeting on March 5, 1987, that missile attacks on Iranian cities would continue until permanent peace on all fronts was achieved. Due to the Russian origin of the missiles, Iran was trying to increase pressure on the Soviet Union.

Iranian leaders and the government tried to blame the Soviet Union and deflect and relieve internal pressure. A number of people and students demonstrated in front of the Soviet embassy and consulate in Tehran and Isfahan, and at the same time, the United Nations and the United States tried to convince Iran to accept the ceasefire Resolution 598.

In fact, protests and diplomatic efforts only began when the first missiles hit Tehran, Isfahan, and Qom. These three cities had never been hit by missiles during the entire eight-year history of the war.

To prevent further damage and disruption to the infrastructure of central cities and to maintain the peace of the population living in these cities, all of Iran’s diplomatic power was utilized. Immediately after the first missiles hit Tehran, Iran asked international organizations to mediate in this matter to prevent the war from spreading to the cities. This was referred to as the “War on Cities”; however, this term was never used for cities near the Iraq border, which are mostly inhabited by non-Persian ethnicities.

The Iranian Foreign Ministry asked Pakistan, England, and Libya to act as mediators to stop Saddam’s attacks on central cities. Tariq Aziz rejected England’s mediation in a meeting with the British Foreign Secretary. Colonel Gaddafi’s envoy was also not accepted, and Taha Yasin Ramadan, Saddam’s first vice president, in a meeting with the special envoy of the President of Pakistan, who carried Zia-ul-Haq’s message, stated that “Stopping the war in the cities was the goal, and Iraq announced that it would continue its actions to inflict heavy blows on Iran until a solution was found to end the war.” [1]

Due to the erosion of the war in Afghanistan and the financial bankruptcy of the Soviet Union [2], the Soviet Union decided to end the war in Afghanistan earlier. Therefore, by selling long-range missiles to Iraq, the Soviet Union showed its intention to end Iran’s support for the Afghan guerrillas more seriously.

Here, it is necessary to clarify that the Tabas incident was, in fact, the bombing of the Afghan Mujahideen logistics line through Iranian territory in Tabas. The Soviets were informed that the U.S. was delivering military equipment and logistics to Iran in Tabas, which Iran was then passing to the Afghan Mujahideen. Tabas served as a transit station for U.S. aid to the Mujahideen inside Iran. After the Soviet bombing, then-President Bani Sadr ordered the re-bombing of the area to destroy evidence and prevent scandal. Years later, during a Friday prayer in Tehran, Hojjatoleslam Rafsanjani accused Bani Sadr of this act, leading to the clarification of the incident’s reality. The American forces could not have launched a rescue operation for their hostages 500 kilometers from Tehran, and no unseen aid or supernatural forces were involved in the destruction of the helicopter and weapons.

If the Iran-Iraq War had ended before the Afghan War, Soviet income from arms sales—especially to Iraq—would have ceased, and the costs of the Afghan War would have financially crippled the Soviet Union.

On the other hand, Iraq’s remaining resources and interests required that permanent peace and Resolution 598 be accepted by Iran. However, Iran only wanted to stop attacks on central cities. The Soviet Union, due to its large logistical commitments and financial struggles with the Afghan war, intended to end the Afghan conflict first. The Soviet Union’s main source of revenue to continue fighting the Afghan Mujahideen was through arms sales to Iraq (and to a lesser extent to Iran). Therefore, ending the Iran-Iraq War before the Afghan war would have resulted in a financial catastrophe for the USSR. The Soviets effectively prevented the war from ending until their withdrawal from Afghanistan. During negotiations with the U.S. in Geneva on the terms of a safe Soviet withdrawal, they demanded guarantees from the U.S. and Iran (supporters of the Mujahideen) to avoid casualties and counterattacks during their exit.

The United States also supported ending the Iran-Iraq War for two main reasons. First, the war’s escalation in the Persian Gulf threatened oil routes from Kuwait, Bahrain, and Saudi Arabia. By proposing Resolution 598, the U.S. aimed to neutralize this threat to the global energy market. Second, the U.S., by exposing and pressuring those involved in Israeli arms smuggling to Iran, aimed to dismantle the Iranian-Israeli arms network. Ari Ben Menashe (author of Blood Money) was the whistleblower behind this exposure.

In reality, neither Iran nor Iraq played decisive roles in ending the war. The Soviet Union, by equipping Iraq, aimed to pressure Iran and accelerate the end of the war. Without expanding the conflict into Persian cities, Iraq and the USSR could not have forced Ayatollah Khomeini to accept the ceasefire—what became known as “drinking from the poisoned chalice.”

The War’s End and Strategic Symbolism

The final chapter of the eight-year war concluded after the 53-day missile exchange between cities and the handover of Faw Island to Iraq at midnight on April 21, 1988. Saddam Hussein launched two final missiles at Qom, delivering an implicit message to Iran’s leadership, especially those based in Qom.

The continued war and the massive human and economic toll it took on Iran’s border regions, contrasted with the minimal impact on central areas, can only be explained by the different roles assigned to Persian central Iran and non-Persian regions.

Ayatollah Mousavi Ardebili’s statement reveals the Iranian leadership’s intent: the war along the Iraq border would continue, but it must not extend into the country’s interior cities.

During those 53 days, 1,746 people were killed and 8,183 wounded [4], while more than one million people were killed on both sides over the eight years. The war could have ended in its first year with fewer than 2,000 deaths.

Iran’s direct war losses since 1981, calculated at 7 tomans per dollar, amounted to 3,810 billion tomans—equivalent to $440 billion (based on 1980s dollar values). This figure equals approximately 25 years of oil sales to China (based on current contracts). The war’s cost was more than ten times the nation’s oil revenue. If Iraq’s expenses were similar, at least $1 trillion was gained by the arms suppliers during a time of global recession.

These financial statistics do not include the human costs from internal displacement, refugees, and the long-term social effects. Cities like Karaj, Varamin, Fardis, Mehrshahr, and others are now home to displaced people who lost land, culture, and livelihoods. Their forced integration into the central economy left deep scars, including linguistic and cultural assimilation, reliance on the rentier state, and the collapse of agriculture and infrastructure in their home regions.

Although the war lasted 2,888 days, it was the 53-day missile campaign on Persian cities that decided its fate.

Throughout the war, the peripheral populations—Arabs, Lors, and Kurds—sought explanations for its continuation. Under heavy censorship and repression, their demands remained confined to private discussions and never shaped official policy.

Economic Centralization and Internal Colonialism

Looking at the war’s aftermath, it becomes evident that its prolongation was economically motivated.

The transfer of industrial and economic centers to Persian-majority areas, often lacking economic justification, revealed entrenched ethnic favoritism. Decisions to move major industries such as steel, machinery, and automobile manufacturing to cities like Isfahan, Arak, Mashhad, Kerman, and Rafsanjan were made by officials from the same Persian ethnicity.

Engineer Mahloji once explained the relocation of the Bandar Abbas Iron and Steel Factory to Isfahan by citing “exaggeration of a hypothetical threat.” Yet a missile from southern Iraq could reach both cities equally. This revealed the strategic pretext used to benefit Persian regions at the expense of more logical locations.

As Smedley D. Butler once said, “War is a racket.” For some, it was profitable; for others, it was tragedy.

When the ceasefire was announced, many currency and gold traders in Tehran and Isfahan went bankrupt due to the dramatic fall in the price of the dollar and gold. Some reportedly committed suicide. War and devastation in the non-Persian periphery directly correlated with economic growth in Persian central Iran. As war impoverished the outer regions, commercial and financial opportunities were funneled into the center.

State support for factory construction and industrial expansion heavily favored cities like Arak, Karaj, Qazvin, Zanjan, Qom, Saveh, Semnan, Isfahan, and Yazd. These cities lacked raw materials, labor access, ports, and export markets. As a result, they became home to uncompetitive, overpriced, and rentier state-run factories. These were later privatized and handed to the regime’s inner circle—a subject further examined in Chapter 4 of Cocolonialism.

Conclusion

Throughout history, warfare has driven economic centralization and the consolidation of power into elite classes in the Western system and ethnic groups in Eastern ontology. This often leads to economic structures that reinforce unproductive large capital at the expense of entrepreneurship and local development. In Iran’s case, the prolonged war led to a concentration of economic and political power within Persian-majority regions, deepening structural inequalities and internal colonial dynamics.

The Persians in modern warfare have avoided direct confrontation with enemies, and the majority of recent conflicts have been executed by proxies and neighboring nations, even though they are inside current Iranian borders. Non-Persians have lived in a colonial state and have been used for the centralization of political, economic, and narrative hegemony. The wars have been used to weaken the natural indigenous power of non-Persian speaking and the relocation of resources and demographic changes. The eight-year Iran-Iraq war and the sudden seizure of war after direct loss to central regions are the evidence.

About the Author

Pejvak Kokabian is the author of Cocolonialism, a book on the colonial condition of non-Persians in Iranian geography.

Farsi version available at https://www.kurdia.net/archives/6236

Sources used

[1] The Fourth Period of the War of the Cities, Yadollah Izadi ,

[2] In one of Brzezinski’s videos, he declares the goal of helping the Mujaheddin fight in Afghanistan to bankrupt the Soviet economy .

[3] Refer to the book Profits of War (Blood Money in farsi), by Ari Ben Manashe. https://www.amazon.com/Profits-War-Inside-U-S-Israeli-Network/dp/1879823012

[4] The Fourth Period of the War of the Cities, Yadollah Izadi, from the Negin Iran series of articles, taken from the Internet Archive, http://www.negineiran.ir/article_6882_962.html

[5] Statistics and figures you should know about the Iran-Iraq war, October 1, 2015 , accessed, http://entekhab.ir/fa/news/227060/

[6] Prof. Mehrdad Izady, On Iraq, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E3uyUNVOn4U

[7] The television series Mr. Dollar portrayed the story of Mr. Farjami, an employee at the Labor Department, who sought to profit by redeeming his personal dollar savings and entering the currency trade market. However, during the period surrounding the adoption of United Nations Resolution 598, the dollar exchange rate plummeted rapidly, causing Farjami to go bankrupt and ultimately be hospitalized. The series effectively illustrated the stark contrast between two modes of existence in Iran at the time: life in Persian-majority central Iran and life in war-torn peripheral regions. It highlighted how, for many people affected by the war, it became evident that the concerns and anxieties of residents in central Persian Iran were not necessarily about the war itself.