Pejvak Kokabian

Reza Pahlavi is a dividing factor in Iranian revolutionary movements, with each point elaborated across three paragraphs.

1. The Conflict Between “Father” and “Citizen” Roles

The sources highlight a fundamental ideological split regarding Pahlavi’s status. Supporters often view him as a “father” figure for all Iranians, a symbol intended to unite various ethnic groups like Kurds, Arabs, and Baluchis. This paternalistic view is seen by some as a necessary moral authority to heal the wounds of a fractured nation.

However, critics argue that this “fatherly” framing is inherently divisive because it implies the Iranian people are “subjects” (ra’iyat) rather than empowered citizens. This dynamic was supposedly rejected permanently during the 1979 revolution. By occupying a role that is perceived as superior to the common person, Pahlavi alienates those who demand a purely horizontal, democratic structure.

Ultimately, the sources suggest that as long as Pahlavi does not view himself as a regular citizen or an equal political figure, he remains a leader of only one specific faction. This prevents him from gaining the broad, inclusive support necessary for a democratic revolution, as many segments of society refuse to return to a relationship based on submission to a central authority.

2. Concentration of Power in the “National Emergency Manual”

A significant point of division involves the “National Emergency Manual” attributed to Pahlavi’s plans. According to the sources, Article 4 of this document grants him the unilateral power to appoint the heads of all three branches of government during a transition period. This centralization of authority mirrors the autocratic structures that many revolutionaries are seeking to dismantle.

Furthermore, the manual specifies that Pahlavi would personally select the members of the “National Uprising Council,” a body intended to function similarly to a revolutionary council. This control over the transitional legislative and executive frameworks suggests a top-down approach to governance.

Critics argue that this framework provides no guarantees for democratic distribution of power. Instead of fostering a collective leadership, the sources indicate that such a plan places immense political power in the hands of one individual, creating deep suspicion among other opposition groups who fear a new era of authoritarianism.

3. Control over the Intelligence and Security Apparatus

The sources identify the proposed management of national security as a major source of friction. In the “National Emergency Manual,” it is stated that the new Intelligence and National Security Organization would be answerable solely to Pahlavi. This setup is explicitly compared to the former SAVAK or the current Ministry of Intelligence.

This plan is divisive because of the historical trauma associated with secret police and state violence in Iran. Since 1925, Iran has been governed by regimes that used violence and intelligence services to suppress the population. Re-establishing a security organ that reports only to a single leader is seen as a regression rather than a reform.

Because there is no clear guarantee that this power would be handed over to the people or a representative body, many activists view this as a red flag. The lack of institutional checks and balances on the security apparatus makes it difficult for Pahlavi to be seen as a unifying figure for those who have suffered under previous intelligence regimes.

4. The Structure of the Proposed Referendum

The method by which Pahlavi proposes to determine Iran’s future government is also a point of contention. The “National Emergency Manual” stipulates that the body responsible for organizing a national referendum would be determined by Pahlavi himself. This raises questions about the neutrality and fairness of the eventual vote.

The choice offered in this proposed referendum—between a “democratic monarchy” and a “democratic republic”—is criticized for being overly restrictive. This binary choice is compared to the 1979 referendum structure, which many feel did not allow for a truly open democratic deliberation.

By controlling both the organization of the referendum and the options presented, Pahlavi is seen as steering the outcome toward his own interests. This perceived lack of transparency and inclusivity in the “emergency” plan divides the opposition, as different groups want a more organic and pluralistic way to decide the country’s future.

5. Unilateral Actions and the Georgetown Meeting

Pahlavi’s history of cooperation—or lack thereof—with other opposition figures serves as a practical example of his divisive nature. The sources mention the Georgetown meeting, which Pahlavi reportedly left unilaterally. This exit is interpreted by critics as a sign that he is unwilling to work within a coalition where he is not the dominant leader.

The source suggests that Pahlavi’s departure was motivated by the fact that others were not “submissive” or “obedient” to his direction. This behavioral pattern reinforces the image of Pahlavi as a figure who expects to lead rather than collaborate, which is a significant barrier to building a unified front against the current regime.

As long as he maintains a position where he is viewed as “superior” to other political actors, he will remain a leader of a single “vein” or branch of the revolutionary movement. This inability to maintain a coalition limits his appeal and prevents him from achieving the general consensus required for a successful democratic transition.

6. The Legacy of Historical Authoritarianism

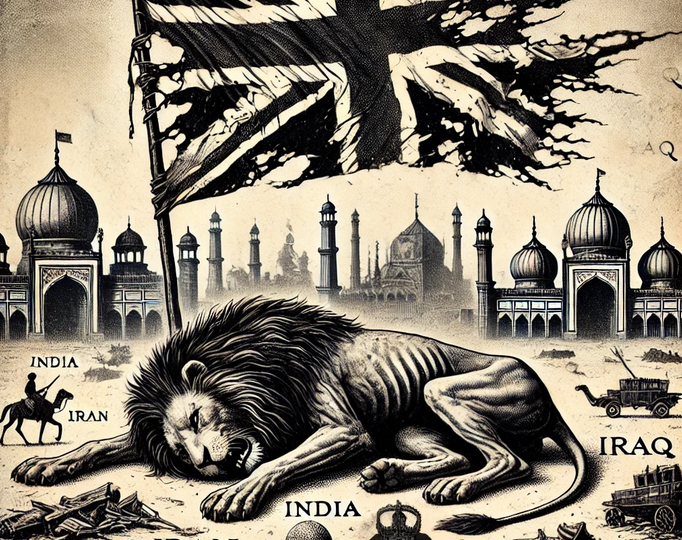

The sources frame the current division within the context of Iran’s modern history of autocratic rule, beginning with the rise of Reza Shah in 1925. Critics argue that the Pahlavi name is inextricably linked to a tradition of state violence and the suppression of the citizenry.

While supporters view the Pahlavi era as a time of progress or stability, others point out that these governments were authoritarian and maintained power through force. This historical baggage makes it difficult for Pahlavi to act as a bridge between different political factions, as his very presence evokes the “poison” of past divisions used by the current regime to discredit the opposition.

Ultimately, the division stems from a lack of guaranteed democratic mechanisms in Pahlavi’s current platform. Without a clear commitment to being an equal citizen and a rejection of concentrated power, the shadow of 20th-century authoritarianism continues to make him a polarizing figure in the eyes of those seeking a clean break from the past.

Think of a group of people trying to rebuild a house that has burned down. One person offers to lead the effort, but they insist on keeping the only set of keys to the tool shed and the blueprints in their pocket, promising to share them only once the foundation is laid. While some trust this leader because of their family’s history of building houses, others are afraid that once the house is finished, the leader will simply lock everyone else out, just as their ancestors might have done. This lack of shared keys and exclusive control over the plans creates a rift among the builders before they even pick up a hammer.