1. Executive Summary

This report examines the significant economic opportunity loss experienced by the Kurdistan region of Iran, stemming from an estimated annual deficit of $3 billion in its gold mining sector. The analysis focuses on quantifying the direct and indirect economic impacts, particularly in terms of lost employment and investment, due to the current management and revenue distribution model of the region’s substantial gold resources. The Kurdistan region, encompassing provinces such as Kurdistan (Sanandaj) and West Azerbaijan (Urmia), is exceptionally rich in gold deposits, with some estimates suggesting these areas hold a significant majority of Iran’s total gold reserves. However, the economic benefits from these resources largely bypass the local population, leading to widespread unemployment, underdevelopment, and social discontent. This report utilizes available data on gold production, such as the Zarshouran mine’s output and employment figures, to model the potential economic gains that could be realized if the region had greater control over its mineral wealth. The $3 billion annual loss figure is treated as the total value of gold extracted from the region, which, if managed differently, could translate into substantial local economic development. The analysis delves into the direct losses, including the number of jobs that could be created in mining and related sectors, and the indirect losses, such as foregone tax revenues, stunted growth in supporting industries, and the environmental and social costs borne by local communities. The findings aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of the economic potential being squandered and to highlight the urgent need for policy reforms that would allow the Kurdistan region to benefit more directly from its natural resources, thereby fostering regional stability and prosperity. The report underscores that the current situation not only represents a significant economic loss for the Kurdish population but also a missed opportunity for broader national economic development and poverty reduction in one of Iran’s most resource-rich yet underdeveloped regions.

2. Gold Reserves and Production in Iran’s Kurdistan Region

2.1. Overview of Gold Resources

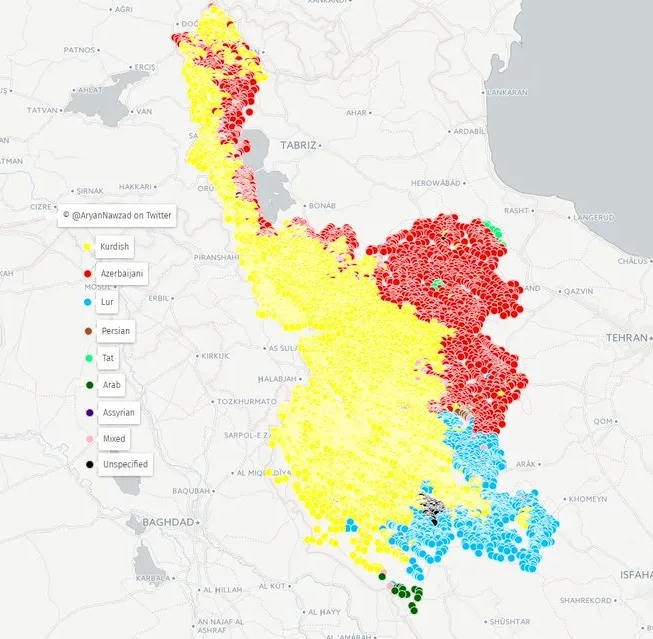

The Kurdistan region of Iran, primarily encompassing the provinces of Kurdistan (Sanandaj) and West Azerbaijan (Urmia), is endowed with substantial gold reserves, positioning it as a significant area for mineral wealth within the country. Various reports and official statements indicate that these two provinces alone may contain a dominant share of Iran’s total gold deposits. For instance, some sources suggest that approximately 65% of Iran’s proven pure gold reserves are concentrated in these western regions . The geological formations in this area are highly favorable for gold mineralization, hosting numerous identified and potential mining sites. The gold-rich belt extends across a wide geographical area, including cities like Saqqez, Qorveh, Takab, Baneh, Mahabad, Sardasht, Oshnavieh, and Piranshahr, indicating a widespread distribution of gold resources beyond just a few isolated mines . The scale of these resources is further highlighted by estimates that just five major mines in the Sanandaj and Urmia provinces are estimated to contain over 330 tons of pure gold . This concentration of wealth underscores the region’s potential to be a major global player in gold production if these resources were fully and optimally exploited with local benefit in mind. The presence of such significant reserves, however, contrasts sharply with the economic conditions prevalent in many parts of the Kurdistan region, where local communities often experience high unemployment and limited access to basic services, raising critical questions about the distribution of benefits derived from these natural assets.

2.2. Key Mining Operations (e.g., Zarshouran, Agh-Darreh)

Several key gold mining operations are located within the broader Kurdistan region of Iran, primarily in West Azerbaijan and Kurdistan provinces, which are central to the country’s gold production. The Zarshouran gold mine, situated near Takab in West Azerbaijan province, is frequently cited as Iran’s largest gold mine and a cornerstone of its mining industry . Recent exploration activities have reportedly increased Zarshouran’s proven gold ore reserves significantly, with extractable gold resources now estimated at 116 metric tons, extending its operational lifespan considerably . This mine is a major producer, with an annual output of around 3 tons of gold and employing approximately 1,250 people directly . Another significant operation is the Agh-Darreh (also spelled Aghra or Agh Darreh) gold mine, also located in Takab, West Azerbaijan. Alongside Zarshouran, Agh-Darreh is a notable contributor to the region’s gold output and has been associated with environmental and health concerns for nearby communities . In Kurdistan province, the Qolqoleh mine in Saqqez is reported to contain significant reserves, with estimates of 8 tons of pure gold and potentially over 100 tons of impure gold . The Sari Gunay (or Sari Guni) gold mine near Qorveh in Kurdistan province is another important asset, with substantial proven reserves and an estimated annual production capacity . These mines, among others like Kervian (Kurvinan) in Saqqez, represent the primary sources of gold extraction in the region, yet their economic impact on local Kurdish communities remains a contentious issue, with frequent reports of limited local employment and benefits .

2.3. Current Production Levels and Potential

Iran’s overall gold production has seen fluctuations and targeted increases over the years. Official figures from various sources indicate an annual gold production ranging from approximately 2-2.5 tons to as high as 7-8 tons nationally in recent years, with ambitions to reach higher targets . A significant portion of this national output originates from the gold-rich Kurdistan region, particularly from mines in West Azerbaijan and Kurdistan provinces. For instance, the Zarshouran mine alone is reported to produce around 3 tons of gold annually . The original reports states that in the Persian year 1401 (2022), an estimated 25 to 27 tons of pure gold were extracted from the two provinces of Kurdistan and West Azerbaijan . This figure represent a substantial share of any reported national total and highlights the immense productive capacity of this region. The potential for increased production is also significant. The Zarshouran mine’s expansion plans, for example, aimed to increase its annual output to 6 tons . Furthermore, discoveries of new gold reserves and the development of new mines, such as those in Saqqez with an estimated 16 tons of proven net gold deposits, point towards a growing production capacity . The Iranian government has previously set targets to increase national gold production to 5 tons per year and eventually to 25 tons per annum under a long-term plan . Given that a large percentage of Iran’s gold reserves are located in the Kurdish provinces, achieving these national targets would heavily rely on maximizing output from this area. However, realizing this full potential in a way that benefits the local population remains a critical challenge.

3. The $3 Billion Annual Economic Opportunity Loss: An Analysis

3.1. Derivation of the $3 Billion Figure

The figure of a $3 billion annual economic opportunity loss in Iran’s Kurdistan region due to gold mining is derived from the estimated total value of gold extracted from the provinces of Kurdistan (Sanandaj) and West Azerbaijan (Urmia). According to sources, these two provinces collectively produced an estimated 25 to 27 tons of pure gold in the 2022 . The calculation to arrive at the $3 billion value is based on a global gold price of $108 million per ton (assuming $3337 per ounce and 32.15 ounces per kilogram, hence $107.284 million per ton, rounded to $108 million in the source) . Multiplying the lower end of the production estimate (25 tons) by $108 million per ton yields $2.7 billion, while the higher end (27 tons) yields approximately $2.916 billion. This substantial sum represents the gross value of the gold extracted. The “opportunity loss” arises from the assertion that if this revenue were invested directly within the Kurdistan region, under local management and for local benefit, it could generate significant economic development, job creation, and improved living standards, which are currently not being realized. The core of the argument is that the current system of resource management and revenue distribution leads to these funds being largely diverted away from the region, thus constituting a lost opportunity for local prosperity. This $3 billion, therefore, serves as a baseline for estimating the scale of potential direct and indirect economic benefits that are being foregone.

3.2. Direct Economic Losses

The direct economic losses stemming from the $3 billion annual opportunity cost in Iran’s Kurdistan region’s gold mining sector primarily manifest as lost employment and foregone investment within the local mining and associated industries. The user’s initial article posits that if the $3 billion generated from gold sales were invested directly in the region, it could create approximately 300,000 sustainable direct jobs, based on a global average of $10,000 capital investment per job . While this specific job creation multiplier can be debated, the underlying principle is that large-scale mining operations, if managed to maximize local employment and procurement, can be significant job creators. The Zarshouran mine, for example, directly employs around 1,250 people for an annual production of 3 tons of gold . Extrapolating this, if the total production from the region is indeed 25-27 tons, and similar employment ratios were maintained with a focus on local hiring, the direct employment in mining could be substantially higher than currently observed. Reports indicate that local communities in these mining areas suffer from high unemployment and that jobs in the mines are often given to individuals from outside the region . This represents a direct loss of livelihood opportunities for the local Kurdish population. Furthermore, direct investment losses include the lack of development of local processing facilities, infrastructure directly related to mining operations (like specialized transport and maintenance services), and limited reinvestment of profits into expanding local mining capacity or exploring new local reserves. The capital generated from these resources, if retained and reinvested locally, could foster a thriving mining ecosystem, but currently, much of this investment potential is lost to the region.

3.3. Indirect Economic Losses

The indirect economic losses resulting from the $3 billion annual opportunity deficit in the Kurdistan region’s gold sector are multifaceted and extend beyond the immediate mining operations, impacting the broader regional economy and social fabric. One significant indirect loss is the foregone tax and royalty revenue that could be collected by local or regional governing bodies if they had greater fiscal autonomy or a more equitable share of the profits. The article suggests that 15% of the state’s share from mining rights (which could be interpreted as taxes or royalties) from the $3 billion revenue would amount to $450 million annually . This substantial sum, if available to local authorities, could be channeled into critical public services such as road construction, water supply, schools, and healthcare, thereby improving living standards and stimulating further economic activity. Another major indirect loss is the reduced economic activity in supporting industries. Mining operations typically generate demand for a wide range of goods and services, including transportation, logistics, equipment manufacturing and maintenance, construction, and professional services. If the mining sector were more integrated with the local economy, these supporting industries would experience significant growth, creating a multiplier effect on employment and income. The original article estimates that for every direct job in mining, at least two indirect jobs could be created in service sectors, potentially leading to 450,000 additional jobs . Furthermore, the lack of local economic empowerment contributes to continued poverty and out-migration from rural areas surrounding the mines, depriving these communities of human capital and further stunting local development. The environmental degradation associated with some mining practices also imposes indirect costs, such as health problems due to pollution and the loss of agricultural productivity, which burden local communities and the regional economy .

4. Direct Economic Impact: Lost Jobs and Investment

4.1. Employment in the Mining Sector

The direct loss of employment opportunities within the mining sector in Iran’s Kurdistan region is a critical consequence of the current management of its gold resources. The Zarshouran gold mine, one of the largest in Iran, employs approximately 1,250 individuals for an annual production of about 3 tons of gold . If the total gold production from the Kurdistan and West Azerbaijan provinces is indeed in the range of 25-27 tons per year, as suggested by the initial user-provided article , a proportional scaling of direct employment (assuming similar labor intensities and operational scales) could potentially support around 10,400 to 11,250 direct mining jobs. However, numerous reports indicate that local communities in these mining areas often face high unemployment rates and are frequently bypassed for employment in these mines, with preference given to workers from other regions or affiliated with specific entities . This practice not only deprives locals of direct income but also fuels social discontent and protests. In the medium to lower economies each billion dollar investment may lead to creation of 50000 job opportunities directly and indirectly. Therefor $3 billion in annual revenue could generate 150,000 direct jobs (based on a $10k to $20k investment per job) is not far from reality and it underscores the significant employment potential if the entire value chain, from extraction to potential local processing and beneficiation, were developed with a focus on labor absorption and local hiring. The current scenario, therefore, represents a substantial loss of direct employment, contributing to economic stagnation and poverty in a region rich in natural resources. The lack of transparency in hiring practices and the concentration of economic benefits outside the local community exacerbate this problem, leading to a situation where the presence of vast mineral wealth does not translate into widespread local prosperity through job creation.

4.2. Investment in Mining Infrastructure and Operations

The Kurdistan region of Iran is losing significant opportunities for direct investment in mining infrastructure and operations due to the current model of resource exploitation. The annual $3 billion in gold revenue, if a substantial portion were reinvested locally, could fund extensive development within the regional mining sector. This includes investment in modernizing existing mining operations to improve efficiency, safety, and environmental standards, as well as exploring and developing new, smaller-scale mines that could be more amenable to local ownership or partnership. Currently, much of the capital expenditure and operational spending for large mines like Zarshouran is likely controlled by national entities or large conglomerates, with limited direct financial flow or reinvestment into the local Kurdish economy beyond basic wage payments to a fraction of the workforce. Investment in downstream activities, such as gold refining, assaying, and jewelry manufacturing, is also sorely lacking. Developing such value-added industries within the Kurdistan region would not only create more jobs but also capture a greater portion of the final value of the gold. Furthermore, investment in critical supporting infrastructure, such as specialized transportation networks for mineral products, power supply for mining operations, and research and development facilities focused on mining technologies suitable for the region, is also limited. The absence of a localized investment strategy means that the region remains primarily an extractive zone, exporting raw or semi-processed materials and losing out on the much larger economic benefits that could be derived from a more integrated and locally focused mining industry. This lack of investment perpetuates a cycle of underdevelopment, where the region’s resources are depleted without a corresponding build-up of local capital, expertise, or industrial capacity.

5. Indirect Economic Impact: Broader Consequences

5.1. Lost Tax and Royalty Revenue for Local Governance

A significant indirect economic loss for the Kurdistan region of Iran is the substantial foregone tax and royalty revenue that could otherwise be available for local governance and development. The user’s initial article estimates that 15% of the state’s share from mining rights, derived from the $3 billion annual gold revenue, would amount to $450 million per year . This figure, while illustrative, highlights the potential fiscal capacity that could be generated if a more equitable system of revenue sharing were in place, allowing local or regional authorities in Kurdistan to directly benefit from the mineral wealth extracted from their land. Such revenue could be a game-changer for local governance, enabling investments in critical public infrastructure, social services, and economic development initiatives tailored to local needs. Currently, it is likely that the majority of taxes and royalties from these mining operations flow to the central government, with a disproportionately small share, if any, being returned to the Kurdistan region for specific local development purposes. This fiscal imbalance contributes to the underfunding of local services, inadequate infrastructure in mining-affected communities, and a general lack of resources for local authorities to address the socio-economic challenges faced by their populations. The inability to capture a fair share of the fiscal benefits from their own natural resources undermines the financial autonomy and development potential of local governments in the Kurdistan region, perpetuating a cycle of dependency and underdevelopment despite the presence of immense mineral wealth.

5.2. Reduced Economic Activity in Supporting Industries

The current management of gold mining in Iran’s Kurdistan region leads to significantly reduced economic activity in a wide array of supporting industries, representing a major indirect economic loss. Mining operations, particularly large-scale ones, typically generate substantial demand for goods and services beyond direct extraction. These include transportation and logistics for moving ore and equipment, manufacturing and maintenance of mining machinery, construction of mine facilities and related infrastructure, provision of specialized technical services (engineering, geological surveying, environmental consulting), and a host of other ancillary services. If the gold mining sector in Kurdistan were more deeply integrated with the local economy and prioritized local procurement, these supporting industries would experience considerable growth, leading to job creation and income generation that extends far beyond the mine gates. The original article suggests a multiplier effect, estimating that for every direct mining job, at least two indirect jobs could be created in service sectors . While the exact multiplier can vary, the principle holds: a thriving mining sector can act as an engine for broader regional economic development by stimulating these linked industries. However, when procurement is centralized or directed towards suppliers from outside the region, or when the scale of operations does not encourage the development of local service enterprises, this potential economic stimulus is largely lost. Local businesses miss out on opportunities to supply the mines, and the region fails to develop a diversified industrial base that could support and benefit from the mining sector, thereby limiting the overall economic impact and perpetuating reliance on a narrow range of economic activities.

5.3. Environmental and Social Costs

The gold mining activities in Iran’s Kurdistan region impose significant environmental and social costs on local communities, which represent a critical, albeit often unquantified, indirect economic loss. Reports from various sources, including local activists and environmental experts, highlight serious concerns regarding the impact of mining operations . These include water contamination from chemicals used in ore processing (such as cyanide, lead, arsenic, and mercury), which can poison water sources essential for drinking, agriculture, and livestock, thereby undermining local livelihoods and posing severe health risks . Soil degradation, destruction of local flora and fauna, and air pollution from mining and processing activities further degrade the environment and reduce its capacity to support traditional economic activities like farming and beekeeping . The social costs are equally concerning. There are widespread complaints from local residents about not being employed in the mines, despite high local unemployment, with jobs often going to individuals from other regions . This fuels resentment and social tension. Furthermore, the influx of outside workers can strain local resources and infrastructure. Perhaps most alarmingly, there are reports of increased incidence of cancer and other health problems in communities living near mining sites, which imposes a heavy burden on affected families and the already strained local healthcare systems . These environmental and social costs are often externalized, meaning they are borne by the local communities and the environment rather than by the mining companies or the entities profiting from the resource extraction. This represents a significant economic loss in terms of degraded natural capital, increased healthcare expenditures, lost agricultural productivity, and diminished quality of life, all of which hinder sustainable development in the region.

6. Factors Contributing to the Economic Opportunity Loss

6.1. Mismanagement and Inequitable Distribution of Profits

A significant factor contributing to the substantial economic opportunity loss in Iran’s Kurdistan region, particularly concerning its gold resources, is the prevalent mismanagement and inequitable distribution of profits generated from mining activities. Reports indicate that despite the region’s rich mineral endowment, local communities often see little to no benefit from the extraction of these resources . Instead, profits appear to be concentrated in the hands of a few, often individuals or entities with strong connections to the central government or the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), rather than being reinvested locally or distributed fairly to the areas from which the wealth is extracted. For example, the Agh-Darreh gold mine, a major operation, is owned by Pouya Zarkan, a company founded by regime insiders Ali Kolahdouz Esfahani and the late Majid Ahmadi-Niri, an IRGC member . These individuals, reportedly residing in Canada, have amassed significant personal wealth from the mine, which produces approximately one ton of gold annually, while the local population in Takab continues to live in poverty . This pattern suggests a systemic issue where the financial gains from mining are siphoned off to benefit a select few, rather than contributing to the broader economic development of the Kurdistan region.

The mechanisms of this inequitable distribution are further highlighted by the alleged transfer of exploitation rights through shell companies, ultimately benefiting these well-connected families . This lack of transparency and accountability in the management of natural resources creates an environment where local interests are marginalized. Furthermore, there are reports of foreign companies, particularly from China and Russia, being granted access to Iran’s gold mines, including those in regions near Kurdistan, as part of broader cooperation agreements . In some instances, these foreign-operated mines employ very few local workers, instead bringing in their own labor force, as allegedly seen with the Mazraeh-Shadi mine in Varzaqan, East Azerbaijan province, which reportedly employed only 20 local workers despite its significant gold ore reserves . This not only deprives locals of employment opportunities but also means that the skills and expertise developed through mining operations do not transfer to the local workforce. The combination of domestic cronyism and foreign exploitation, with minimal local benefit, points to a deeply entrenched system of mismanagement that directly contributes to the $3 billion annual economic opportunity loss by preventing the region from capitalizing on its own natural wealth. The lack of local control over resources and the revenue they generate is a critical impediment to economic self-determination and development in the Kurdistan region of Iran.

6.2. Lack of Local Beneficiation and Value Addition

A critical factor exacerbating the economic opportunity loss in Iran’s Kurdistan region’s gold mining sector is the pervasive lack of local beneficiation and value addition. The region, despite its rich gold deposits, primarily functions as an exporter of raw or semi-processed gold, meaning that the vast majority of the economic value embedded in the final gold products is captured elsewhere. If the $3 billion in annual gold revenue were managed locally with a strategic focus on developing downstream industries, a significant portion of this capital could be invested in establishing refineries, manufacturing facilities for gold jewelry and other gold-based products, and advanced research and development centers for mineral processing within the Kurdistan region itself. This would not only create a multitude of higher-skilled and better-paying jobs compared to direct extraction but would also allow the region to retain a much larger share of the total value generated from its natural resources. The current model, however, sees the gold being shipped out for processing and manufacturing, often to central Iran or international markets, thereby depriving the Kurdistan region of the opportunity to build a diversified and resilient industrial base around its most valuable mineral asset. This absence of a local value chain means that the economic benefits are truncated at the extraction stage, severely limiting the potential for sustainable regional development and perpetuating a dependency on the export of low-value primary commodities. The foregone investment in these value-added activities represents a substantial component of the overall economic opportunity loss, as it directly translates into fewer jobs, less technological development, and a weaker overall economic structure for the region.

6.3. Environmental Degradation and Health Impacts

The economic opportunity loss in Iran’s Kurdistan region due to gold mining is significantly compounded by severe environmental degradation and associated health impacts, which impose substantial long-term costs on local communities and the region’s overall development potential. Gold mining, particularly when not managed with stringent environmental safeguards, can lead to widespread pollution of land, water, and air. A prominent example is the Zarshouran gold mine, where the tailings dam has reportedly resulted in cyanide leakage, posing a serious threat to the local wildlife and potentially contaminating water sources used by nearby communities . Cyanide, a highly toxic chemical often used in gold extraction, can have devastating effects on aquatic ecosystems and can enter the human food chain, leading to chronic health problems. The article from “The New Region” further elaborates on these concerns, noting that the soil brought from mines to separation factories is often mixed with other toxic minerals like lead, arsenic, and mercury, and the waste from the separation process, stored in reservoirs, can seep into the soil and water over time . This contamination can render agricultural land unusable, poison livestock, and pollute drinking water supplies, directly impacting the livelihoods and health of residents.

The health consequences for communities living near these mining operations are a grave concern. Reports indicate a rise in cancer rates in areas like Aghara and Zareh Shuran in Takab city, with specific instances, such as a two-year-old child in Yangi Kand village suffering from cancer, being cited as potentially linked to mining pollution . Mohammad Rasul Sheikhizadeh, a representative of Qorveh and Dehgolan cities in Sanandaj province, stated that in one village in Qorveh, the water supply was poisoned due to gold mining activities, affecting 50 families . These health impacts translate into increased medical costs, reduced labor productivity, and a lower quality of life, all of which detract from the region’s economic well-being. Furthermore, the environmental damage can have long-lasting effects on ecosystems, reducing biodiversity and the potential for sustainable economic activities like agriculture and tourism. The fact that parliamentary investigations have revealed instances where mining companies, such as Pouya Zarkan, allegedly offered bribes to local authorities to ignore necessary environmental safeguards, underscores the systemic nature of this problem . The failure to internalize these environmental and health costs means that the true economic burden of gold mining is borne by the local population, rather than by the mining operators or the entities profiting from the extracted gold, further exacerbating the economic opportunity loss for the Kurdistan region.

7. Comparative Perspectives and Global Benchmarks

7.1. Lessons from Other Mining Regions (e.g., Armenia, Peru)

Examining the experiences of other mining regions globally can offer valuable lessons for the Kurdistan region of Iran. For instance, Armenia, a country with a significant mining sector, has faced challenges regarding environmental protection and equitable benefit sharing, but has also made efforts to improve transparency and community engagement through initiatives like the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI). Armenia’s experience highlights the importance of robust legal frameworks, independent monitoring of environmental impacts, and mechanisms for ensuring that mining revenues contribute to local and national development. Similarly, Peru, a major global producer of gold and other minerals, provides a complex case study. While mining has contributed significantly to Peru’s export earnings, it has also led to severe social conflicts, environmental damage, and disputes over land and resource rights, particularly affecting indigenous communities. Peru’s experience underscores the critical need for meaningful consultation with local communities, respect for indigenous rights, and the establishment of clear benefit-sharing mechanisms that directly support affected populations and regions. These international examples suggest that without strong governance, transparency, and a commitment to sustainable development, mining can exacerbate inequalities and lead to significant social and environmental problems, rather than fostering broad-based prosperity. For the Kurdistan region, these lessons emphasize the necessity of ensuring that local communities are primary beneficiaries of resource extraction, that environmental safeguards are strictly enforced, and that revenues are reinvested in a way that promotes long-term economic diversification and resilience.

7.2. Potential for Regional Development if Resources Were Managed Locally

The potential for regional development in Iran’s Kurdistan region, if its substantial gold resources were managed locally and equitably, is immense. The $3 billion in annual gold revenue represents a transformative capital base that, if retained and strategically reinvested within the region, could catalyze a new era of economic prosperity. Beyond the direct employment in mining, the development of a comprehensive local value chain, including refining, manufacturing, and associated service industries, could create a diverse range of job opportunities, fostering skill development and technological advancement. The original article suggests that such local management could lead to the creation of hundreds of thousands of direct and indirect jobs, significantly reducing unemployment and poverty . Furthermore, a significant portion of the mining revenues, potentially $450 million annually in local tax and royalty income, could be allocated to critical public investments in infrastructure, education, healthcare, and social programs, dramatically improving the quality of life for the Kurdish population . This could lead to a reversal of out-migration, as improved economic prospects and public services make the region more attractive for both its current residents and potential returnees. The establishment of a robust local economy, underpinned by the sustainable management of mineral wealth, could also enhance the region’s economic autonomy and bargaining power. Ultimately, local management of resources offers the prospect of translating the Kurdistan region’s vast underground wealth into tangible, above-ground improvements in the lives of its people, fostering a more equitable, prosperous, and self-determined future.

8. Conclusion and Recommendations

The economic analysis presented in this report underscores a stark reality: Iran’s Kurdistan region, despite its vast gold reserves, is experiencing a significant annual economic opportunity loss estimated at $3 billion. This deficit is not merely a financial figure but represents a cascade of lost potential in terms of employment, investment, local development, and improved living standards for its population. The current model of resource management, characterized by centralized control and an inequitable distribution of profits, effectively drains the region of the capital necessary for its own development. Direct economic losses manifest as foregone employment opportunities for potentially hundreds of thousands of individuals and a critical lack of investment in local mining infrastructure and value-added industries. Indirectly, the region suffers from diminished tax and royalty revenues for local governance, stunted growth in supporting economic sectors, and the unmitigated burden of environmental degradation and health impacts.

To address this critical situation and unlock the Kurdistan region’s economic potential, a fundamental shift in the management of its mineral resources is imperative. The following recommendations are proposed:

- Decentralization of Resource Management and Revenue Sharing: Implement policies that ensure a significantly larger portion of the revenues generated from gold mining in the Kurdistan region is retained and managed locally. This includes establishing transparent and equitable royalty and tax regimes that directly benefit local and regional governments.

- Promotion of Local Beneficiation and Value Addition: Encourage and invest in the development of downstream industries within the Kurdistan region, such as gold refineries, jewelry manufacturing, and advanced material production, to capture a greater share of the value chain and create higher-skilled employment.

- Prioritization of Local Employment and Procurement: Mandate policies that prioritize the hiring of local labor and the procurement of goods and services from local businesses for all mining operations in the region, fostering local economic linkages and capacity building.

- Strengthening Environmental and Social Safeguards: Enforce stringent environmental regulations for mining operations, ensure comprehensive environmental impact assessments, and mandate robust community consultation processes. Allocate dedicated funds from mining revenues for environmental protection, remediation, and community development programs.

- Transparency and Accountability: Establish transparent mechanisms for revenue collection, allocation, and expenditure, potentially through initiatives like the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), to ensure that mining benefits are managed accountably and reach the intended beneficiaries.

- Investment in Diversification and Sustainable Development: Utilize a portion of the mining revenues to invest in economic diversification initiatives, such as agriculture, tourism, and renewable energy, to build a more resilient and sustainable regional economy less dependent on finite mineral resources.

By adopting such measures, it is possible to transform the Kurdistan region’s gold mining sector from a source of economic disparity into an engine for inclusive and sustainable development, ensuring that its rich natural endowments truly benefit the people who call this resource-rich land their home.