This piece continues the discussion initiated by the author in 2018 regarding the Referendum of Rojhelat.

Introduction

Democracy is often interpreted as the rule of the majority, but this principle alone cannot ensure a just and stable society. Without protective institutional mechanisms, an unrestrained majority can impose its will over minority rights, resulting in oppression and instability. This phenomenon, termed the tyranny of the majority, is intensified by nationwide mass referendums—tools that populist leaders exploit to manipulate public emotions and pursue authoritarian goals.

In contrast, territorial voting systems (electoral voting systems) offer a vital mechanism for safeguarding minority rights, fostering dialogue, and ensuring the long-term sustainability of democracy. In nations like Brazil, composed of regions with immense ethnic diversity, this approach has significantly aided in managing varied identities. This article contends that territorial voting is crucial to prevent majority dictatorship, while direct mass referendums can lead to populism and the emergence of totalitarian leaders. Drawing on historical studies and political theories, it presents nine core arguments—each bolstered by supplementary reasoning—for the superiority of territorial voting over mass referendums in such a diverse country.

Territorial Voting Defends Minority Rights

A fundamental task of democracy is to balance the majority’s desires with the protection of minorities. Without institutional limits, a dominant majority—such as urban residents of southeastern Brazil—could enact policies that marginalize or eliminate minorities, like the Amazon’s indigenous peoples.

James Madison warned in Federalist Papers No. 10 that mass democracy could lead to division and oppression, where the majority enacts laws favoring itself at the expense of minorities (Madison, 1788, p. 57). Territorial voting neutralizes this danger by distributing voting power across Brazil’s diverse federal regions, ensuring governance reflects a broader consensus rather than the dominance of a single ethnic or regional group.

Conversely, collective referendums pave the way for majority tyranny; for example, if a 1967-style referendum in Brazil had entrusted indigenous rights to a non-indigenous majority. Electoral systems, by mandating regional representatives to engage in dialogue and consider minority interests, prevent reckless majority domination in this ethnically vibrant nation.

Territorial Voting Promotes Inclusive Representation

These systems can employ mechanisms like proportional representation to ensure Brazil’s federal regions—from Afro-Brazilians in Bahia to German descendants in Santa Catarina—have a voice in legislation. However, direct referendums render these minorities vulnerable to the dominant voice of the majority, such as the populous southeast, while overlooking remote areas like Roraima.

Territorial Voting Reduces Discriminatory Legislation

By channeling decisions through representatives accountable to the ethnic diversity of their regions, these systems avoid passing laws that overtly favor one group over another. Brazil’s 1988 Constitution, crafted with regional participation, secured indigenous land rights—an outcome unlikely in a referendum dominated by urbanites. Historically, mass referendums have reinforced regional biases and entrenched inequality.

Territorial Voting Strengthens Dialogue, Unlike Mass Referendums That Stifle It

Democratic decision-making should be grounded in reason and dialogue, not impulsive motives, royal decrees, governmental edicts, or directives from a centralized bureaucracy. In Brazil, electoral systems enable regular debates and expert consultations among federal regions, aligning policies with diverse ethnic perspectives before implementation.

In contrast, mass referendums reduce complex issues—like Amazon deforestation—to simplistic “yes or no” votes, often swayed by emotion rather than logic. Furthermore, individuals decide on the geography, culture, language, and identity of others without knowledge. For instance, why should a Shia Azerbaijani Turk vote on a Sunni Baloch textbook or economic zones and fuel policies in Balochistan, and vice versa? The only justification for universal mass referendums is that resources, instead of being managed by territorial regions, are controlled and exclusively expended by Tehran’s sprawling central bureaucracy.

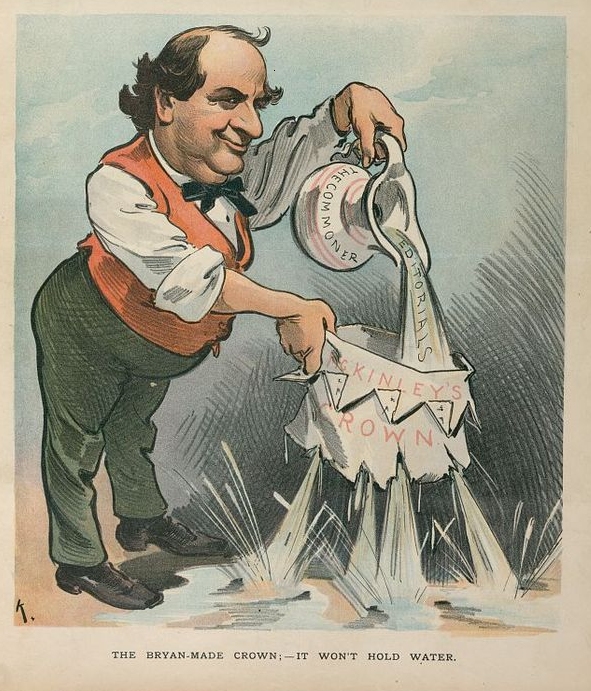

Nadia Urbinati notes that populist leaders misuse referendums to bypass legislative oversight, framing issues in a reactive, instantaneous manner (Urbinati, 2014, p. 113). A national mass referendum on land in Brazil could have misled urban voters with misinformation, disregarding indigenous needs. In Iran’s 1979 revolution, revolutionary leftists and rightists forced a referendum with a yes-or-no vote on the Islamic Republic, replacing one authoritarian system with another. Today, among opposition groups, especially monarchists, calls to determine governance via referendum and mass voting resurface, signaling their intent to ride populist emotional waves and exploit nostalgia crafted by affiliated media.

Territorial voting, by ensuring institutional dialogue and expert input from regional representatives, prevents rash decisions incompatible with a country’s diversity.

Territorial Voting Provides Opportunities for Reflection

Unlike referendums demanding immediate votes, territorial voting allows policies to evolve through regional legislation. Brazil’s Bolsa Família project improved over years with feedback from regional residents and experts, balancing urban and rural needs—something a populist-fueled referendum might have rejected, ignoring deprived regions.

Territorial Voting Benefits from Institutional Expertise of Regional Specialists

Regional representatives draw on Brazil’s historical context—like land reforms—to maintain stability and long-term interests. In Brazil, 1960s regional dialogues laid the groundwork for subsequent policies, whereas an instant referendum might have disregarded these experiences, igniting ethnic tensions.

Territorial Voting Facilitates Multilateral Participation

Territorial representatives consult diverse groups—regional leaders, indigenous communities, urban planners—ensuring balanced policies. Brazil’s ethanol program aligned regional interests, unlike referendums that designate populous regions as the nation’s sole voice. Mass referendums prioritize populist narratives over practical outcomes. For example, why should an Azerbaijani Turk bear the cost of the Iranrud project when their own roads and electricity infrastructure remain lacking?

Territorial Voting Prevents Demagogic Mobilization

Populist leaders gain power by emotionally mobilizing the masses, using mass democracy as a tool to entrench authority and wield it oppressively. In Brazil, territorial voting filters leadership through regional institutions, mandating approval from diverse ethnic communities rather than relying solely on national appeal and inflated charisma.

History demonstrates that mass referendums aid authoritarian rule. Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt document how Adolf Hitler eliminated political opposition through direct mass votes (Levitsky & Ziblatt, 2018, p. 94). In Brazil, a populist could have exploited a referendum to bypass regional constraints, as Hugo Chávez did in Venezuela, driving a resource-rich nation into ruin despite wealth surpassing Brazil’s. In Iran, the unitary system (centralized internally, tributary and colonial externally) since the first Pahlavi era has similarly squandered wealth, mirroring Venezuela.

Territorial Voting Prevents Power Concentration in a Charismatic Leader and Preserves Regional and Ethnic Balance

Governance is conditioned on respecting rights and forging broad coalitions, serving as a tool against authoritarian resurgence. In a country like Brazil, leaders must build coalitions across territorial regions, reducing demagogues’ influence. The 1985 transition from military rule succeeded through regional alliances, unlike a mass referendum that might have empowered a populist leader. Direct votes disregard this balance.

Territorial Voting Curbs Media Populism and Decentralizes Media Structures

Requiring sustained regional interaction, these systems diminish the influence of sensationalist media, often controlled by specific ethnic groups (and shaped by foreign interests planning future power shifts). Brazil’s 2002 elections showed how Lula managed regional diversity, whereas a referendum could have amplified urban media distortions, silencing marginal and rural ethnic voices.

Territorial Voting Prevents Populist Oversimplification

Populist leaders excel at simplifying and dumbing down issues for an unaware majority. Using simple, deceptive slogans (free utilities), empty promises, and even unstable short-term handouts (subsidies and cash distribution) to maximize votes is their best tactic. Complex policy decisions—like infrastructure development, monetary policy, and international trade—require precision, expertise, and dialogue. Mass referendums offer overly simplistic solutions to multifaceted issues.

Jan-Werner Müller argues that populists present issues in binary terms (black or white) to manipulate emotions (Müller, 2016, p. 72). A referendum on Amazon highways in Brazil might have pitted “progress” against “preservation,” ignoring ethnic and environmental nuances with slogans.

As Iran’s religious regime nears collapse, some groups (security system remnants and monarchists) have made the binary “us or disintegration” a dominant theme in their affiliated media. Territorial voting neutralizes these risks, advancing policymaking through informed regional representatives rather than uninformed national pressure and media sensationalism.

Territorial Voting Avoids Hypocrisy and Dualism

Regional dialogue dismantles populists’ binary traps. In Brazil, territorial debates on education budgets yielded moderate solutions, whereas a referendum might have reduced it to “more” or “less,” overlooking ethnic inequalities populists exploit. In Iran, the mother tongue issue has fallen into such a trap, with the national parliament wielding numerical majority as a cudgel, turning a simple, globally resolved matter into a tool for executing and criminalizing non-Persian-speaking teachers.

Territorial Voting Reduces the Risk of Majority Radicalization

Unsupervised mass voting can radicalize majority groups (e.g., Iran’s “Shaban Bimokhs”), especially when fear or misinformation—such as over territorial resource disputes—drives emotions. Territorial voting prevents drastic shifts by requiring federal regional approval.

Kurt Weyland illustrates how Chávez’s referendums destroyed democracy with unchecked constitutional changes (Weyland, 2014, p. 137), silencing regions and their voices. In Brazil, absent territorial mediation, the southeastern majority could have pushed authoritarian policies under a democratic guise. Territorial voting curbs extremism, ensuring no ethnic group dominates without broad support.

In Crises, Territorial Dialogue Tempers Rash Impulses

Brazil’s 1990s economic stabilization via Congress avoided extremism, unlike a referendum that might have inflamed urban fears. Direct mass votes lack these protective mechanisms.

Territorial Voting Encourages Gradual Change

In Brazil, incremental shifts align with ethnic diversity. In Iraq, the federal system emerged from ongoing dialogues, though pressure from Iran and Baghdad has prevented Kurdistan’s federal region from voting on its constitution. In federal systems, states and regions have their own constitutions.

Brazil’s 1988 Constitution, shaped by territorial consensus, avoided the abrupt disruptions a referendum might have caused, such as sudden power grabs by a specific ethnic group.

Territorial Voting Deters Authoritarian Centralization and Reduces Bureaucratic Monopoly

Totalitarian rulers use mass referendums to centralize power, removing limits under a democratic veneer. Before Erdoğan’s consolidation in Turkey, over 80 provinces wielded decision-making power, crafting better economic policies for their regions. Van could easily attract foreign investment by promoting real estate and tourism, but now, with power centralized in Ankara, strategies serve the central rulers’ whims, tastes, and ethnicity. In Brazil, territorial voting disperses power across regions, making monopoly difficult.

Milan Svolik proves how Vladimir Putin cemented control through mass referendums (Svolik, 2012, p. 84). In Brazil, a populist could have used a referendum to override regional autonomy, crafting superficial legitimacy.

Territorial Voting Preserves Separation of Powers Through Decentralized Decision-Making

It mandates negotiation among governing institutions elected from below, keeping power decentralized and accountable. Regional constraints—like Brazil’s state courts—curb centralization, unlike mass referendums that bypass these safeguards for authoritarian aims.

Territorial Voting Sustains Institutional Competition

Competition among regions prevents monopolistic dominance. Healthy rivalry between Brazil’s northeast and south limits authoritarianism, unlike referendums that hand power to an unrestrained national populist.

Territorial Voting Prevents “Mobocracy” and Majority Tyranny in Uninformed Decision-Making

Democratic governance must be guided by reason, not mob chaos. Territorial voting imposes regional limits to avoid reckless decisions in such nations.

Athens’ democratic collapse partly stemmed from mass-driven choices leading to disaster (Thucydides, 1910, p. 204). In Brazil, emotional masses could yield unpredictable outcomes, like resource allocation favoring populous regions’ intents. All mines and subsurface resources in Iran’s non-Persian territories serve interests contrary to their true owners, exploited rapaciously by Tehran’s regime or pre-sold wholesale as tribute to foreign companies.

Territorial voting ensures leaders are chosen based on experience and regional approval, not fleeting emotions.

Territorial Voting Restrains Hasty Reactions

Regional authorities resist populist whims. Brazil’s gradual environmental laws prevented mass exploitation calls, unlike a referendum that might have been swayed by short-term profiteering.

Territorial Voting Maintains a Long-Term Perspective

Regional planners emphasize strategy. Brazil’s WWII governance balanced needs, unlike a referendum that might have led to isolationism. Unfortunately, mass votes sacrifice foresight for instant relief.

Territorial Voting Ensures Continuity in Long-Term Development Policies

Specialized regional committees craft cohesive policies. Brazil’s SUS health system reflects a history of continuous regional input, unlike a referendum that could yield scattered ethnic outcomes.

Territorial Voting Guarantees Governance Stability in Crises

In crises, stable leadership is vital. Mass democracy risks fear-driven volatility. Territorial voting advances measured decisions through regional dialogue.

Weimar Republic referendums enabled Hitler’s rise with emergency powers (Arendt, 1951, p. 128). Brazil’s electoral system—e.g., post-1964 coup reforms—historically navigated crises without collapsing into totalitarianism. The need for regional coalitions makes territorial voting resilient against authoritarian capture.

Territorial Voting Resists Opportunistic Exploitation

Decentralized power and political decentralization prevent exploitation and plunder. Brazil’s 1985 democratization via elections avoided authoritarian relapse, unlike a referendum that could hasten centralization in a crisis.

A national referendum led by urban voters distant from these realities might prioritize exploitation over preservation, as could have occurred with populist voting on Vale dam projects.

Territorial Voting Strengthens Local Knowledge

Regional governments leverage local expertise—like Mato Grosso’s farming skills—to optimize resources. This local approach contrasts with referendums, where a national majority, unfamiliar with regional conditions, might impose inefficient policies like a blanket deforestation ban without considering sustainable logging.

Territorial consensus becomes necessary, deterring populist leaders from short-term resource exploitation. The 1970s Itaipu dam project succeeded through regional negotiations, whereas a referendum might have fueled a populist hydropower rush, ignoring displaced groups like the Guarani. Direct votes favor national greed over regional stewardship. A prerequisite for territorial voting should be regional resource management—full ownership and legal respect for territorial resource control, subjecting the center and unrelated outsiders to modern consent requirements. True resource ownership by locals makes central bureaucrats and officials more democratic, requiring regional legislative approval for any resource extraction.

Brazil’s Federal Regions Benefit from Territorial Voting

With resources like Amazon timber or Minas Gerais iron ore, territorial voting empowers local legislative bodies and regional governments to manage these assets efficiently. This contrasts with mass referendums that risk uniform policies disregarding regional diversity.

Territorial Voting, Like the U.S. Electoral System, Grants Equal Rights to Regions

Regardless of population—e.g., Iowa with one-tenth of California’s—each state has an equal say.

Territorial Voting Aligns Resource Policies with Local Conditions

Through elected representatives, territorial voting enables regions to tailor mineral and natural resource policies to their environmental and territorial realities. For instance, Pará’s mining company regulates gold extraction with indigenous and riverine community involvement, blending economic profit with sustainable development and local benefit. Currently, nearly all Kurdistan’s mines in Iran are controlled by British, Kazakh, and European firms, with unclear central authorities granting concessions—likely via bribes—yielding no evident revenue return to the lands and peoples of Qorveh, Takab, Bukan, and Saqqez, home to four of Iran’s key gold mines. Western acquiescence to Iran’s colonial crimes in peripheral regions proves that unchecked resource plundering by foreigners comes at the cost of ignoring central government atrocities in these areas.

For detailed analysis, examples and applications, please see the author’s book Cocolonialism.

References

Arendt, Hannah. The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1951.

Levitsky, Steven, and Daniel Ziblatt. How Democracies Die. New York: Crown Publishing, 2018.

Kokabian, Pejvak, Cocolonialism, Library and Archive Canada, 2022, https://www.amazon.com/dp/0995296421/

Kowsar, Nikahang, The Princes Entourages, https://nkowsar.substack.com/p/the-princes-entourage-a-leadership, 2024.

Madison, James. The Federalist Papers No. 10. New York: J. and A. McLean, 1788.

Müller, Jan-Werner. What Is Populism? Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016.

Svolik, Milan W. The Politics of Authoritarian Rule. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Thucydides. History of the Peloponnesian War. Translated by Richard Crawley. London: J. M. Dent, 1910.

Urbinati, Nadia. Democracy Disfigured: Opinion, Truth, and the People. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014.

Weyland, Kurt. Making Waves: Democratic Contention in Europe and Latin America since the Revolutions of 1848. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Referendum of Rojava and Legal Mechanisms. Available at: https://www.kurdia.net/archives/2235

Why Are the Iranian Intelligence and Monarchists Pahlavi Allies? Available at: https://vision.kurdia.net/archives/113.